The Bash shell

A user introduction to the Bash shell

AI workshop

join cohort #1

Bash is (as of today) the de facto shell on most systems you’ll get in touch with: Linux, macOS, and the WSL on Windows 10.

Update: macOS since Catalina (fall 2019) uses Zsh

There are historical reasons that made Bash the most popular shell in the world. Back in 1989, when its was first released, the tech world was very different. At that time, most software in the UNIX world was closed source. Unix itself was proprietary and closed source.

To use a UNIX system you had to use a shell.

The most popular shell at the time was closed source and proprietary, you had to pay to use it. It was the Bourne shell, available under the /bin/sh command. It was called “Bourne” because its creator was Steve Bourne.

Richard Stallman in those years with the GNU Project (and later on Linux) was about to revolutionise everything, starting the Open Source revolution. The GNU Project needed a shell, and, with the help of the Free Software Foundation, Bash was born. Heavily inspired by the Bourne Shell, Bash means Bourne-again shell and it is one key ingredient of the GNU Project, and probably one of its most successful pieces of software that we still use today.

Bash could run all scripts written for sh, which was a mandatory feature for its adoption, and it also introduced many more features, since the very early days, offering a better experience to its users. Since those early days, Bash gained lots of improvements. This tutorial describes the most popular and useful things you can do with it.

First steps in Bash

Since Bash is the default shell in many systems, all you need to start a bash shell is to

- log in to the system, if it’s a server

- open your terminal, if it’s your computer

See my macOS terminal guide for more info on using your terminal on a Mac.

As soon as you start it, you should see a prompt (which usually ends with $).

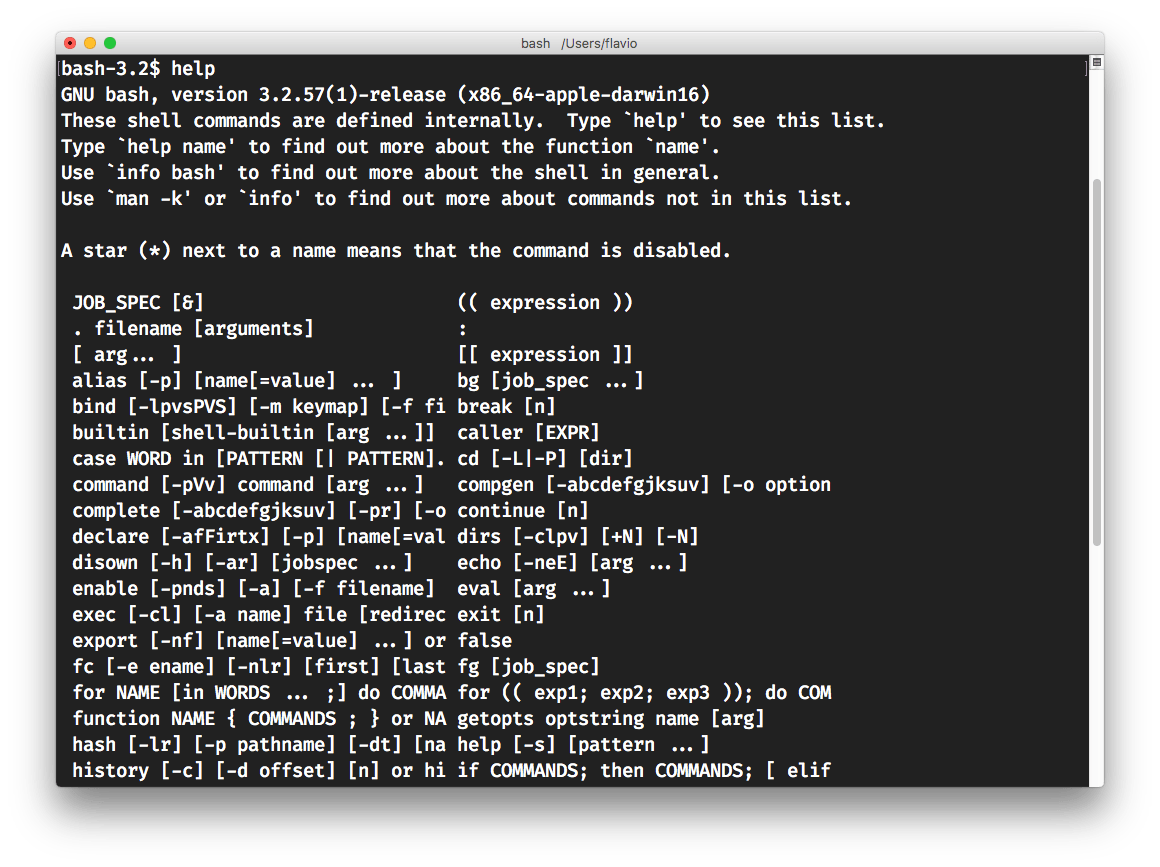

How do you know the shell is running bash? Try typing help and pressing enter.

See? We just told Bash to execute the help command. This command in turns shows you the version of Bash you are running and a list of commands you can use.

Warning: see the version I have there? It’s 3.2.57. This is the default Bash version shipped in macOS, which does not include a higher release for licensing issues. This Bash version is from 2014. Install the latest Bash 5.x using Homebrew, by typing

brew install bash.

More often than not you’ll never use any of the commands listed in the bash help, unless you are creating shell scripts or advanced things.

99% of the day to day shell use is navigating through folders and executing programs like ls, cd and other common UNIX utilities.

Navigating the filesystem

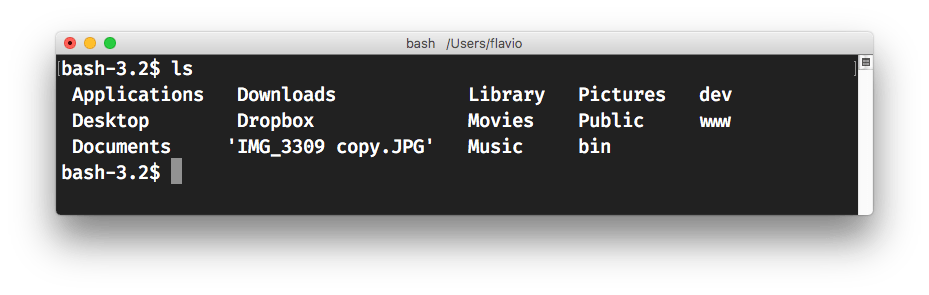

To navigate through the filesystem you will use the ls command. It’s available in the /bin/ls, and since Bash has the /bin folder in its paths list, you can just type ls to use it.

ls lists the files in the current folder. You usually start from your home folder, which depends on the system but on macOS is under /Users. My home folder is in /Users/flavio. This is not Bash related, it’s more of a UNIX filesystem thing, but arguments overlap and if you’ve never used a shell it’s good to know.

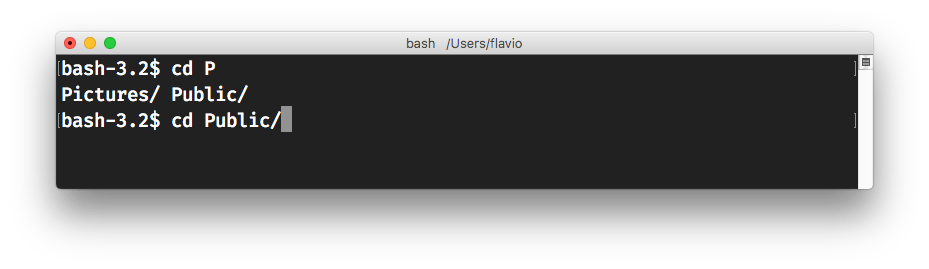

To navigate to other folders you use the cd command, followed by the name of the folder you want to move to:

cd Documentscd .. goes back to the parent folder.

Depending on your Bash configuration, you will see your current folder shown before the prompt (the $ symbol). Or you might not, but you can always know where you are by typing pwd and pressing enter.

pwdmeans pathname of working directory

Command line editing

When you are writing your commands in the shell, notice that you can move left and right with the arrow keys. This is a shell feature. You can move around your commands, press the backspace button and correct commands. Pressing the enter key tells the shell to go and let the system execute the command.

This is normal and accepted behavior, but something that probably made “wow” the early UNIX users.

Keyboard combinations allow you to be quick at editing without reaching for the arrow keys:

ctrl+dto delete the currently selected characterctrl+fto go to the character on the rightctrl+bto go to the character on the left

Autocompletion

A nice feature of Bash when moving around the file system is autocompletion. Try typing cd Doc and press the tab key to make Bash autocomplete that to cd Documents. If there are multiple choices for those first characters Bash will return you the list, so you can type a couple more characters to help it remove the ambiguity and press tab again to complete.

The shell can autocomplete file names, but also command names.

Shell commands

Using the shell we can run commands available on the system. We can prefix the commands with the full path (e.g. /bin/ls to list files in a folder) but the shell has the concept of path so we can just type ls and it knows where most commands are found (and we can add folders to this path by configuring it).

Commands accept arguments. For example ls /bin will list all files in the /bin folder.

Parameters are prefixed by a dash -, like ls -a which tells ls to also show hidden files. Hidden files as a convention are files (and folders) starting with a dot (.).

Common shell commands

There are a lot of commands preinstalled on any system, and they vary considerably depending if it’s Linux / macOS or even the Linux distribution you are running.

However let’s do a brief roundup of the most common shell commands you can run. Those are not provided by shells per se, but rather they are command line commands you can invoke through shells.

Any time you have problems, like you don’t know what a command does, or you don’t know how to use it, use man. It lets you get the help for all of the commands I will list, and more. Run man ls for example.

These are filesystem commands:

lsto list filescdto change folderrmto remove a file or foldermvto move a file to another folder, or change a file namecpto copy a filepwdto show the current working directorymkdirto create a folder

Every file on a Unix filesystem has permissions. chmod allows you to change those (not going into it now), and chown allows you to change the file owner.

cat, tail and grep are two super useful commands to work with files.

pico, nano, vim and emacs are commonly installed editors.

whereis on macOS shows where a command is located on the system.

There are many more commands, of course, but those are a few you might run into more often.

Executing commands

ls and cd are commands, as I mentioned, which are found in the /bin folder. You can execute any file, as long as it’s an executable file, by typing its full path, for example /bin/pwd. Commands don’t need to be in the /bin folder, and you can run executable files that are in your current folder using the ./ path indicator.

For example if you have a runme file in your /Users/flavio/scripts folder, you can run

cd /Users/flavio/scriptsand then run ./runme to run it.

Or you could run /Users/flavio/scripts/runme from Bash, wherever your current folder is.

Jobs

Whenever you run a command, if it’s a long running program, you will have your shell completely owned by that command. You can kill the command using ctrl-C .

At any time you can run jobs to see the jobs you are running, and their state.

$ jobs

Job Group State Command

1 72292 stopped ftpAnother useful command is ps which lists the processes running.

$ ps

PID TTY TIME CMD

19808 ttys000 0:00.56 /usr/local/bin/fish -l

65183 ttys001 0:04.34 -fish

72292 ttys001 0:00.01 ftptop shows the processes and the resources they are consuming on your system.

A job or process can be killed using kill <PID>.

Command history

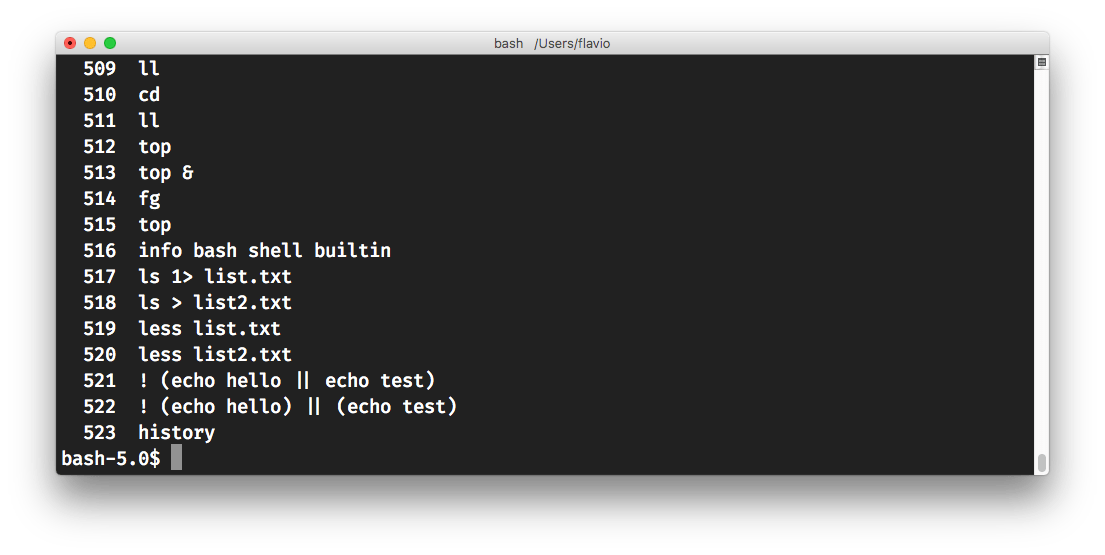

Pressing the up arrow key will show you the history of the commands you entered. Again, this is a shell feature. Pressing the down arrow key will let you navigate back and forth in time to see what commands you entered previously, and pressing enter will let you run that command again.

This is a quick access to the command history. Running the history command will show you all the commands entered in the shell:

When you start typing a command, Bash can autocomplete it by referencing a previously entered command in the history. Try it by pressing esc followed by tab.

To be honest I find the Fish shell implementation of this to be much better and easier

Setting your default shell

There are many more shells other than Bash. You have Fish, ZSH, TCSH, and others. Any user on the system can choose its own shell.

You set your default login shell by running the chsh -s chsh -s /bin/bash command. You’ll almost never need to do that, unless it was previously changed, for example with Fish:

chsh -s /usr/local/bin/fishCustomizing Bash

I noted before that you might (or might not) see your current working directory in the Bash prompt. Where is this determined? In the Bash configuration!

There’s a bit of confusion here because Bash uses a different configuration file for different scenarios, and it also reads multiple configuration files.

Let’s give some order to this confusion. First, there’s a big distinction whether Bash is initialized as a login shell or not. By login shell we mean that the system is not running a GUI (Graphical User Interface) and you log in to the system through the shell. That’s the case of servers, for example.

In this case, Bash loads this configuration file:

/etc/profileand then looks in the user home folder and looks for one of these files, in order, executing the first one it finds:

~/.bash_profile

~/.bash_login

~/.profilewere ~ means your home folder (it’s automatically translated by Bash)

This means that if there’s a .bash_profile, ~/.bash_login and ~/.profile are never run, unless explicitly executed in .bash_profile.

If instead of being a login shell Bash is run like I do with macOS, for example, as a normal application, the configuration files change. Bash loads first /etc/bash.bashrc, then ~/.bashrc.

Environment variables

Sometimes you have programs that use environment variables. Those are values that you can set outside of the program, and alter the execution of the program itself. An API key, for example. Or the name of a file.

You can set an environment variable using the syntax

VARIABLE_NAME=variable_valueThe value can contain white spaces, by using quotes

VARIABLE_NAME="variable value"A bash script can use this value by prepending a dollar sign: $VARIABLE_NAME.

Also other programming languages commands can use environment variables, for example here’s how to read environment variables with Node.js.

The system sets up some environment variables for you, like

$HOMEyour home folder$LOGNAMEyour user name$SHELLthe path to your default shell$PATHthe path where the shell looks for commands

You can inspect their value by prepending echo to them:

echo $LOGNAME # flavio

echo $HOME # /Users/flavioA special environment variable: $PATH

I mentioned the $PATH variable. This is a list of folders where the shell will look into when you type a command. Folders are separated by a colon : and they are written in order - Bash will look into the first, search for the command you asked for, and run it if it finds it. Otherwise if goes to the next folder and so on.

My path is currently:

bash-5.0$ echo $PATH

/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin: /bin:/usr/sbin: /sbin:/usr/local/go/binYou typically edit this in the ~/.bashrc file by prepending or appending items:

PATH = "$PATH:/Users/flavio/bin"Aliases

Using aliases we can set up shortcuts for common commands. You can give a quick name to a complex combination of parameters, for example.

You define an alias using the syntax

alias <alias>=<command>if there’s a space in the command you use quotes:

alias <alias>="<command>"One alias I commonly add to my system is ll:

alias ll="ls --al"You normally define aliases in your ~/.bashrc file.

Just be careful with quotes if you have variables in the command: using double quotes the variable is resolved at definition time, using single quotes it’s resolved at invokation time. Those 2 are different:

alias lsthis="ls $PWD"

alias lscurrent='ls $PWD'$PWD refers to the current folder the shell is into. If you now navigate away to a new folder, lscurrent lists the files in the new folder, lsthis still lists the files in the folder you were when you defined the alias.

Advanced command line features

Wildcards

ls and many other commands can make great use of wildcards. You can list all files starting with image:

ls image*Or all files ending with image:

ls *imageor all files that contain image inside the name:

ls *image*Redirecting output and standard error error

By default, commands started in the shell print out both the output and errors back to the shell. This might not be what you want. You can decide to write the output to a file instead.

Actually, to a /different file/, because in Unix even the screen is considered to be a file. In particular,

0identifies the standard input1identifies the standard output2identifies the standard error

You can redirect the standard output to a file by appending 1> after a command, followed by a file name.

Using the same technique you can use 2> to redirect the standard error.

There is a shortcut > for 1>, since that is used quite a lot.

Example:

ls 1> list.txt 2> error.txt

ls > list.txt 2> error.txtAnother shortcut, &>, redirects /both/ standard output and standard error to a file.

ls &> output.txtAnother frequent thing is to redirect standard error to standard output using 2>&1.

Running a command in the background

You can tell Bash to run a program in the background without it taking control of the shell, by appending & after it:

top &

topis a command that lists the processes running, ordered by most resource consuming.

The application that would normally get control of the shell, is now started but nothing seems to happen. You can bring it back into focus by typing fg (aka foreground), but now we’re entering in the realm of processes and jobs which is a big topic on its own, but a quick overview:

When a command is running you can use ctrl-Z to pause it and bring it to the background. The shell comes back again in the foreground, and you can now run bg to move resume execution of that previously paused job.

When you are ready to go back to it, run fg to bring back that program in the foreground.

You can see all processes running using ps, and the list shows all the processes pid numbers. Using the paused process pid, you can bring to foreground a specific command, for example fg 72292. Same works for bg.

Queuing commands

You can instruct Bash to run a command right after another ends by separating them with a semicolon:

cd /bin; lsYou can repeat this to queue multiple commands in the same line.

Output redirection

A program can receive input from any file using the < operator, and save to a file the output using the > operator:

echo hello > result.txt

wc < result.txtwc is a command that counts the words it receives as input.

Pipe

Using pipes, any command output can be used as input for a second command. Use the | operator to combine the two. In this example, wc gets its input from the output of echo hello:

echo hello | wcGrouping commands

Use && to combine two commands using “and”. If the first command executes without problems, run the second, and so on.

Use || to combine two commands using “or”. If the first command executes without problems the second does not run.

! negates the next logical operation:

$ echo hello && echo test

hello

test

$ echo hello || echo test

hello

$ ! echo hello || echo test

hello

testYou can use parentheses to combine expressions to avoid confusion, and also to change the precedence:

$ ! (echo hello) || (echo test)

hello

test

$ ! (echo hello || echo test)

helloProgramming shells

One of the best features of a shell like Bash is its ability to create programs with it, by basically automating commands execution.

I’m going to write a separate guide on Bash scripting soon, which will be separate from this tutorial because the topic is really more in-depth than what I want to add in this introductory Bash guide.

A quick intro though: a script is a text file that starts with a line that indicates that it’s a shell script (and what shell it requires), followed by a list of commands, one per line. Example:

#!/bin/bash

lsYou can save this as a file myscript and make it executable using chmod +x myscript, and run it using ./myscript (./ means “current folder”).

Shell scripting is outside of the scope of this post, but I want you to know about this. Scripts can have control structures and many other cool things.

This same scripting strategy works for other shells, like Zsh:

#!/bin/zsh

lsI wrote 20 books to help you become a better developer:

- Astro Handbook

- HTML Handbook

- Next.js Pages Router Handbook

- Alpine.js Handbook

- HTMX Handbook

- TypeScript Handbook

- React Handbook

- SQL Handbook

- Git Cheat Sheet

- Laravel Handbook

- Express Handbook

- Swift Handbook

- Go Handbook

- PHP Handbook

- Python Handbook

- Linux Commands Handbook

- C Handbook

- JavaScript Handbook

- CSS Handbook

- Node.js Handbook