The JavaScript Event Loop

The Event Loop is one of the most important aspects to understand about JavaScript. This post explains it in simple terms

- Introduction

- Blocking the event loop

- The call stack

- A simple event loop explanation

- Queuing function execution

- The Message Queue

- ES6 Job Queue

Introduction

The Event Loop is one of the most important aspects to understand about JavaScript.

I’ve programmed for years with JavaScript, yet I’ve never fully understood how things work under the hoods. It’s completely fine to not know this concept in detail, but as usual, it’s helpful to know how it works, and also you might just be a little curious at this point.

This post aims to explain the inner details of how JavaScript works with a single thread, and how it handles asynchronous functions.

Your JavaScript code runs single threaded. There is just one thing happening at a time.

This is a limitation that’s actually very helpful, as it simplifies a lot how you program without worrying about concurrency issues.

You just need to pay attention to how you write your code and avoid anything that could block the thread, like synchronous network calls or infinite loops.

In general, in most browsers there is an event loop for every browser tab, to make every process isolated and avoid a web page with infinite loops or heavy processing to block your entire browser.

The environment manages multiple concurrent event loops, to handle API calls for example. Web Workers run in their own event loop as well.

You mainly need to be concerned that your code will run on a single event loop, and write code with this thing in mind to avoid blocking it.

Blocking the event loop

Any JavaScript code that takes too long to return back control to the event loop will block the execution of any JavaScript code in the page, even block the UI thread, and the user cannot click around, scroll the page, and so on.

Almost all the I/O primitives in JavaScript are non-blocking. Network requests, Node.js filesystem operations, and so on. Being blocking is the exception, and this is why JavaScript is based so much on callbacks, and more recently on promises and async/await.

The call stack

The call stack is a LIFO queue (Last In, First Out).

The event loop continuously checks the call stack to see if there’s any function that needs to run.

While doing so, it adds any function call it finds to the call stack and executes each one in order.

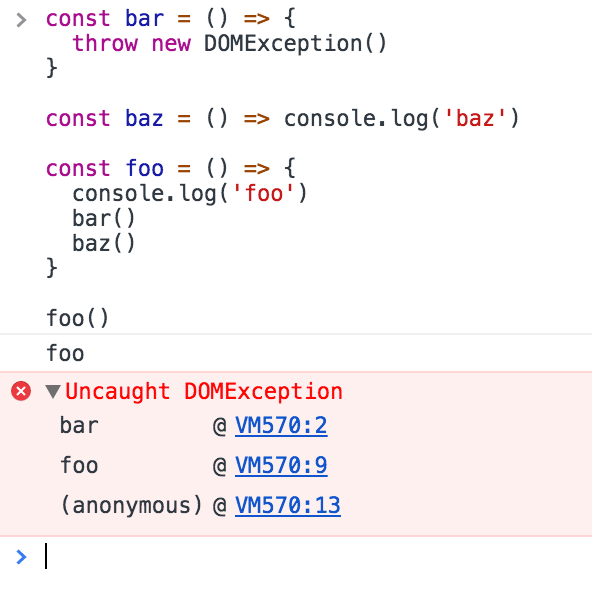

You know the error stack trace you might be familiar with, in the debugger or in the browser console? The browser looks up the function names in the call stack to inform you which function originates the current call:

A simple event loop explanation

Let’s pick an example:

I use

foo,barandbazas random names. Enter any kind of name to replace them

const bar = () => console.log('bar')

const baz = () => console.log('baz')

const foo = () => {

console.log('foo')

bar()

baz()

}

foo()

This code prints

foo

bar

baz

as expected.

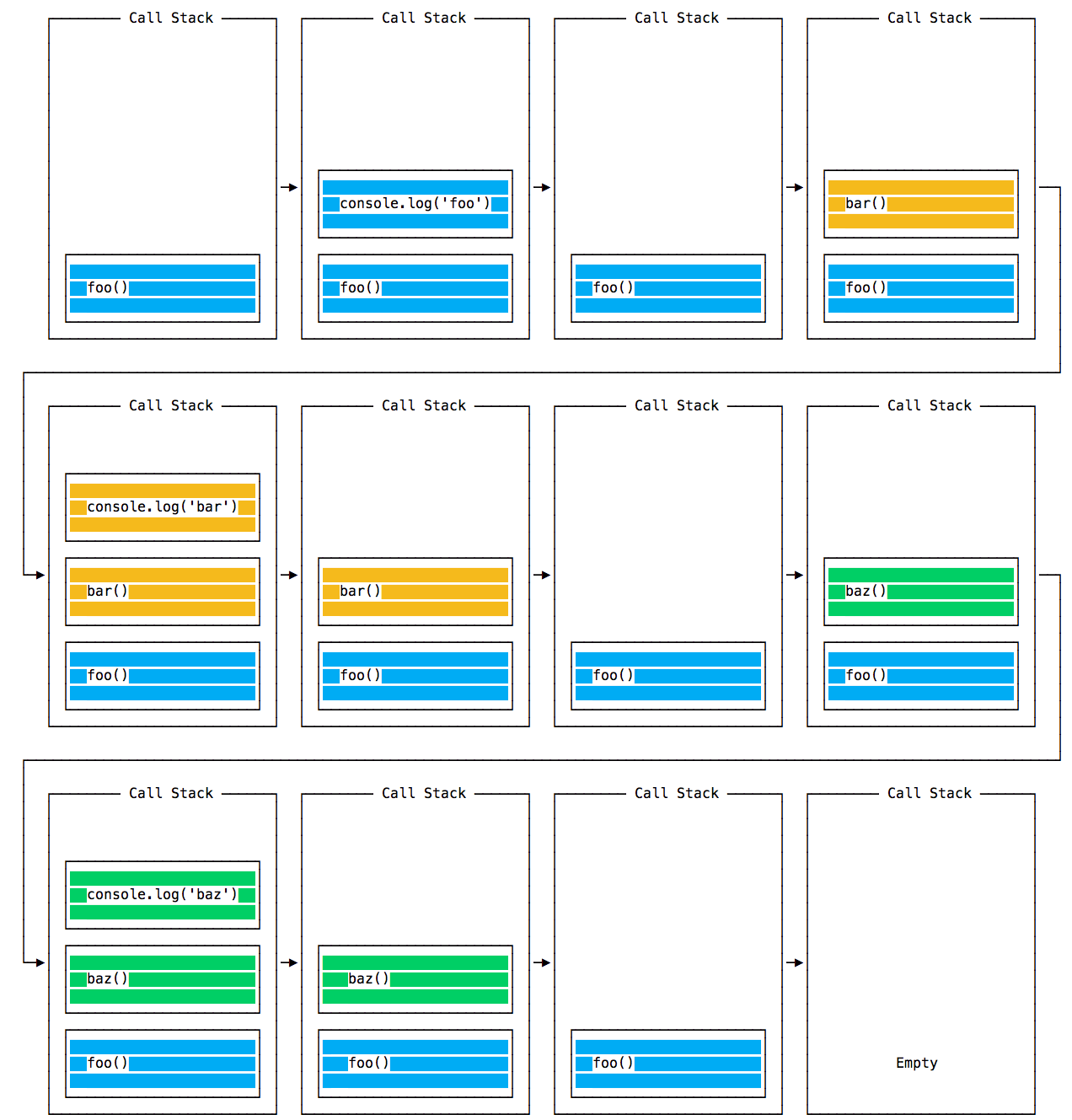

When this code runs, first foo() is called. Inside foo() we first call bar(), then we call baz().

At this point the call stack looks like this:

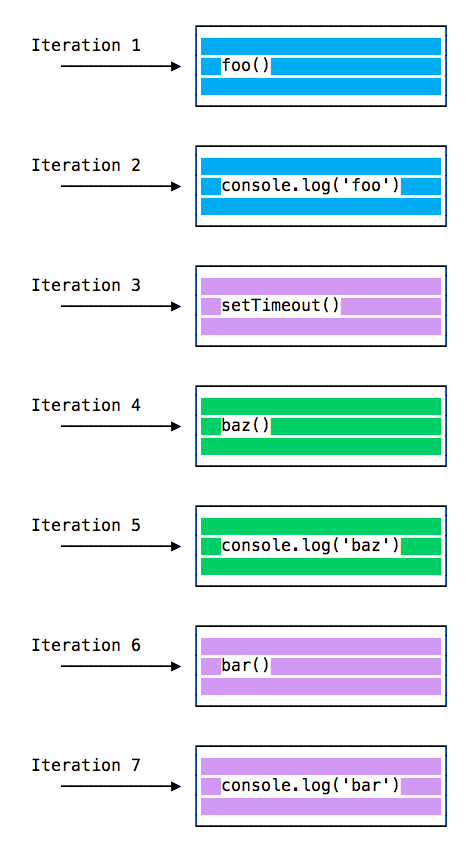

The event loop on every iteration looks if there’s something in the call stack, and executes it:

until the call stack is empty.

Queuing function execution

The above example looks normal, there’s nothing special about it: JavaScript finds things to execute, runs them in order.

Let’s see how to defer a function until the stack is clear.

The use case of setTimeout(() => {}), 0) is to call a function, but execute it once every other function in the code has executed.

Take this example:

const bar = () => console.log('bar')

const baz = () => console.log('baz')

const foo = () => {

console.log('foo')

setTimeout(bar, 0)

baz()

}

foo()

This code prints, maybe surprisingly:

foo

baz

bar

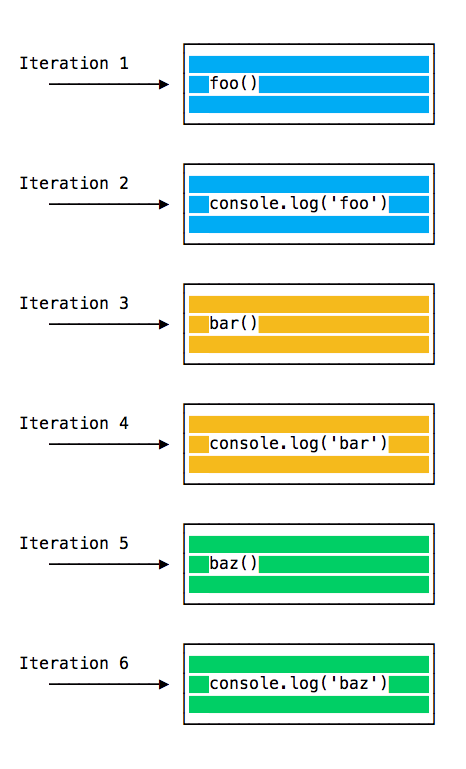

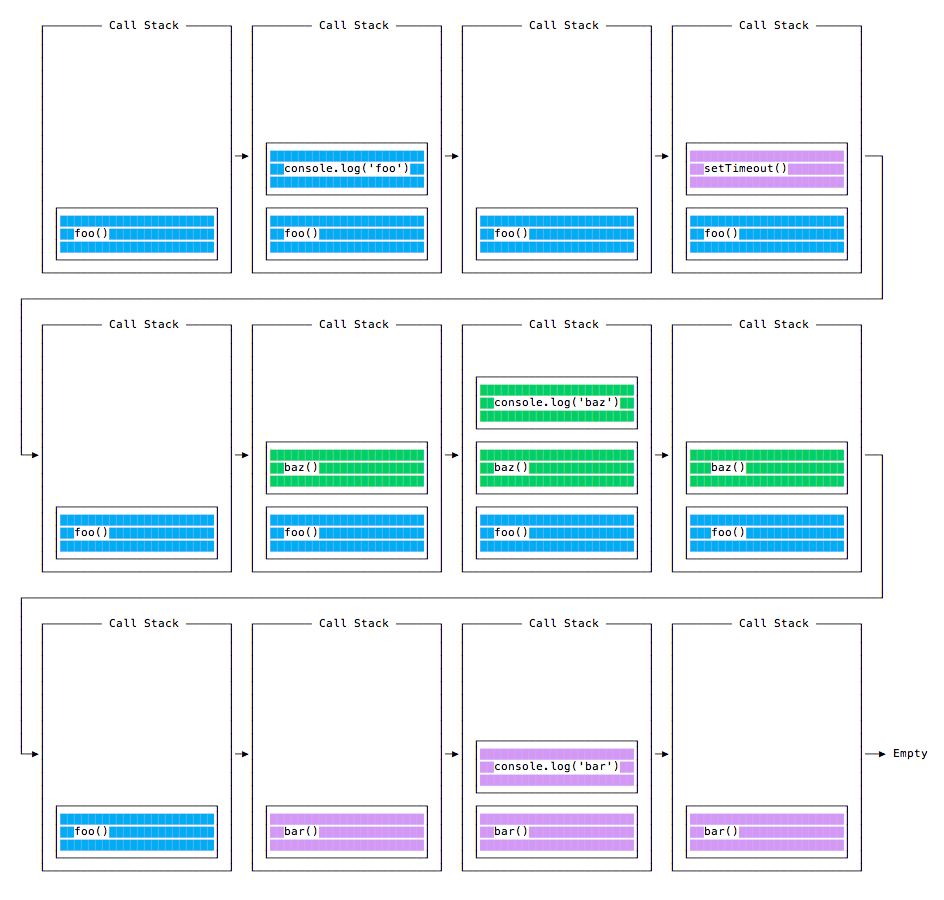

When this code runs, first foo() is called. Inside foo() we first call setTimeout, passing bar as an argument, and we instruct it to run immediately as fast as it can, passing 0 as the timer. Then we call baz().

At this point the call stack looks like this:

Here is the execution order for all the functions in our program:

Why is this happening?

The Message Queue

When setTimeout() is called, the Browser or Node.js start the timer. Once the timer expires, in this case immediately as we put 0 as the timeout, the callback function is put in the Message Queue.

The Message Queue is also where user-initiated events like click or keyboard events, or fetch responses are queued before your code has the opportunity to react to them. Or also DOM events like onLoad.

The loop gives priority to the call stack, and it first processes everything it finds in the call stack, and once there’s nothing in there, it goes to pick up things in the message queue.

We don’t have to wait for functions like setTimeout, fetch or other things to do their own work, because they are provided by the browser, and they live on their own threads. For example, if you set the setTimeout timeout to 2 seconds, you don’t have to wait 2 seconds - the wait happens elsewhere.

ES6 Job Queue

ECMAScript 2015 introduced the concept of the Job Queue, which is used by Promises (also introduced in ES6/ES2015). It’s a way to execute the result of an async function as soon as possible, rather than being put at the end of the call stack.

Promises that resolve before the current function ends will be executed right after the current function.

I find nice the analogy of a rollercoaster ride at an amusement park: the message queue puts you at the back of the queue, behind all the other people, where you will have to wait for your turn, while the job queue is the fastpass ticket that lets you take another ride right after you finished the previous one.

Example:

const bar = () => console.log('bar')

const baz = () => console.log('baz')

const foo = () => {

console.log('foo')

setTimeout(bar, 0)

new Promise((resolve, reject) =>

resolve('should be right after baz, before bar')

).then(resolve => console.log(resolve))

baz()

}

foo()

This prints

foo

baz

should be right after baz, before bar

bar

That’s a big difference between Promises (and Async/await, which is built on promises) and plain old asynchronous functions through setTimeout() or other platform APIs.

→ I wrote 17 books to help you become a better developer:

- C Handbook

- Command Line Handbook

- CSS Handbook

- Express Handbook

- Git Cheat Sheet

- Go Handbook

- HTML Handbook

- JS Handbook

- Laravel Handbook

- Next.js Handbook

- Node.js Handbook

- PHP Handbook

- Python Handbook

- React Handbook

- SQL Handbook

- Svelte Handbook

- Swift Handbook

Also, JOIN MY CODING BOOTCAMP, an amazing cohort course that will be a huge step up in your coding career - covering React, Next.js - next edition February 2025