Visualize your local Git contributions with Go

Tutorial on writing a Git stats analysis CLI tool using Go

LEARN GIT (including rebase and more) with my GIT MASTERCLASS

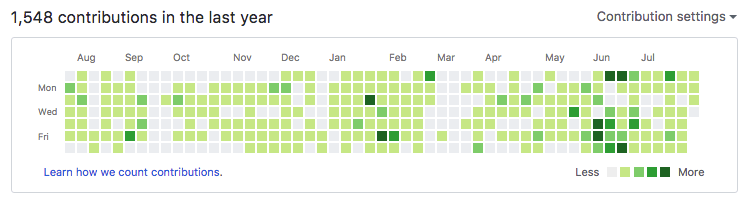

A few years ago I built an Electron + Meteor.js + gitlog desktop app that scanned my local Git repositories and provided me a nice contributions graph, like the one shown on GitHub.com:

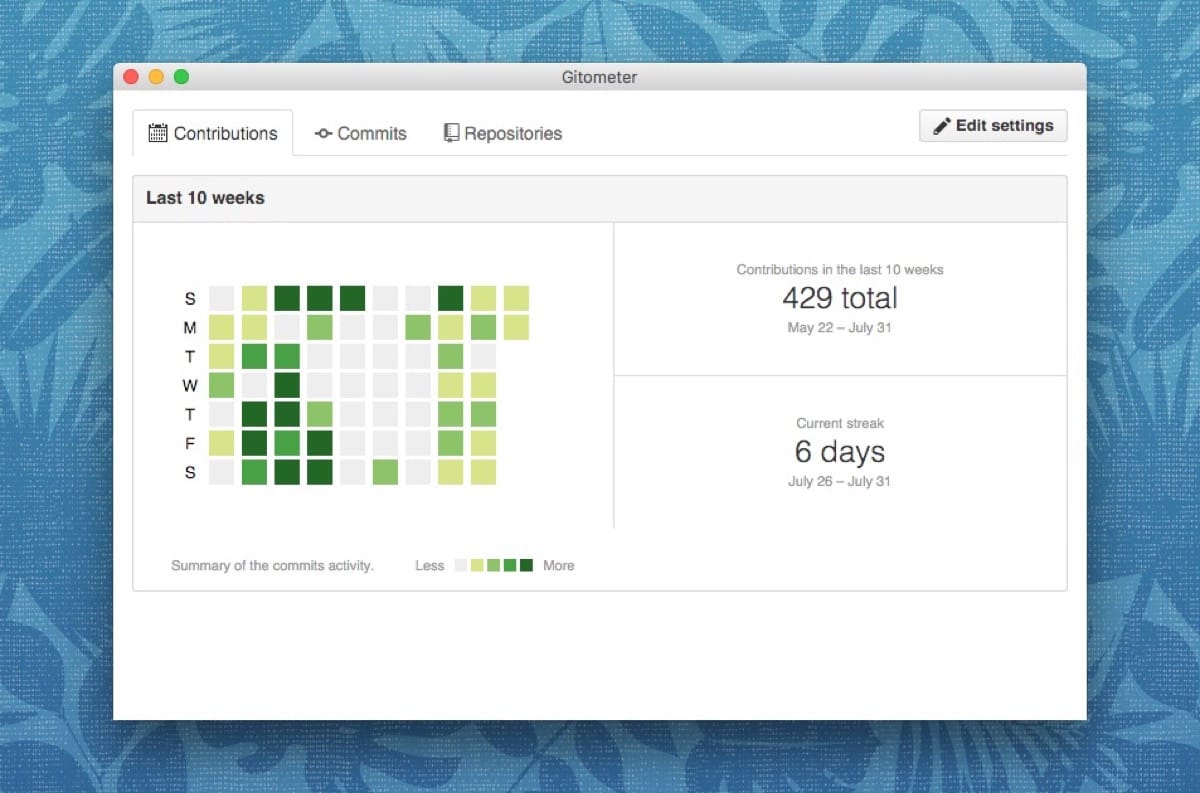

That was before every single app used Electron, and I really disliked this approach due to the generated app size, 50x bigger if compared to the WebKit-based MacGap. Anyway, it looked like this, with a GitHubbish UI:

I found it useful because not all my projects were (are) on GitHub, some are on BitBucket or GitLab, but all the code I work on is on my laptop, so that’s the “single source of truth” when it comes to contributions.

The app still runs, but it’s unreleased to the general public.

Today I decided to port this as a Go console command, since I still find the concept nice.

What I’m going to build in this article 🎉

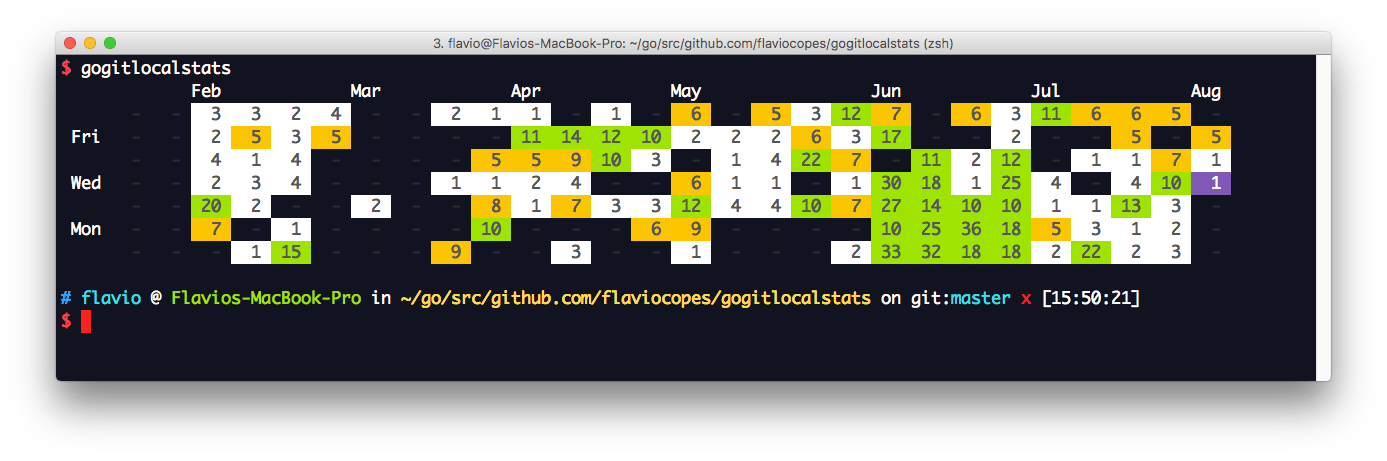

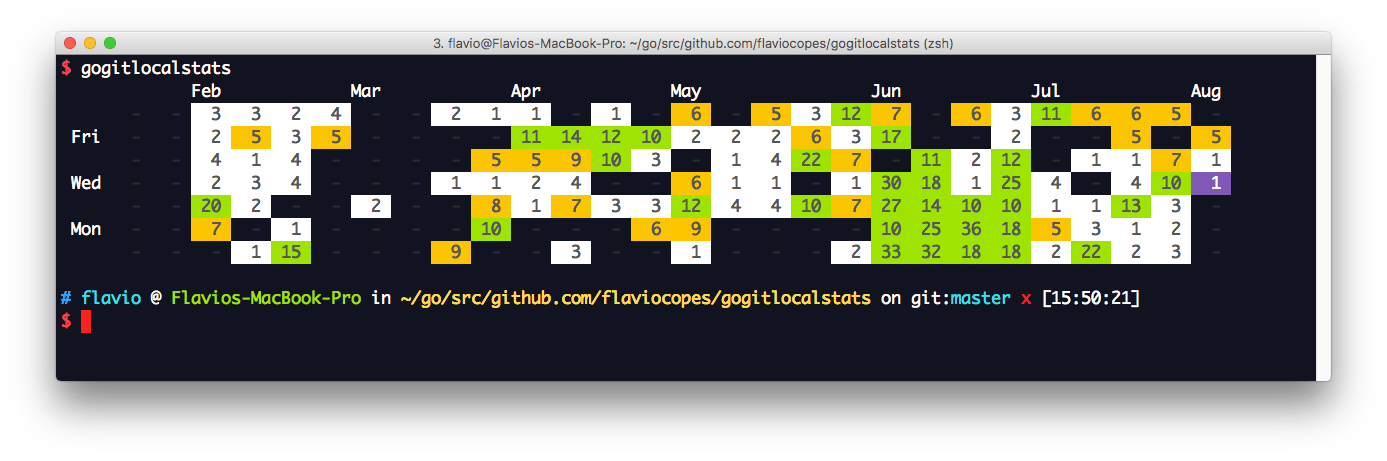

A CLI command that generates a graph similar to

Where to find this code

The code is on this Gist: https://gist.github.com/flaviocopes/bf2f982ee8f2ae3f455b06c7b2b03695

First steps

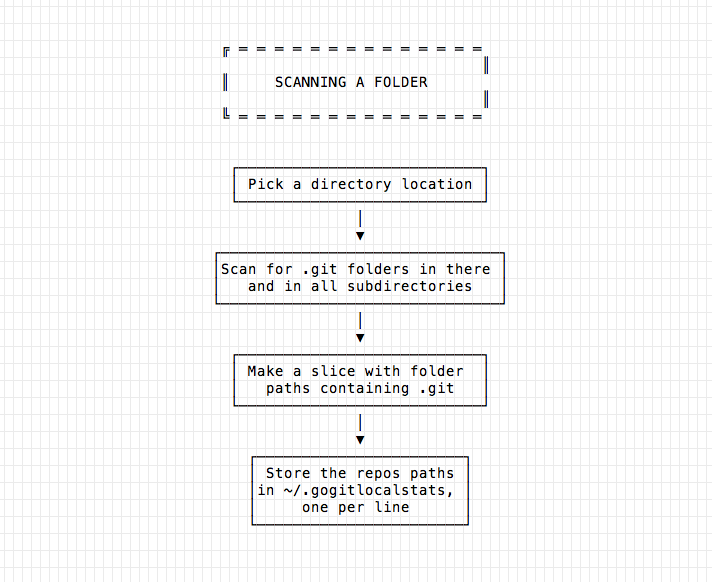

I divided the task in 2 parts:

- Acquire a list of folders to scan

- Generate the stats

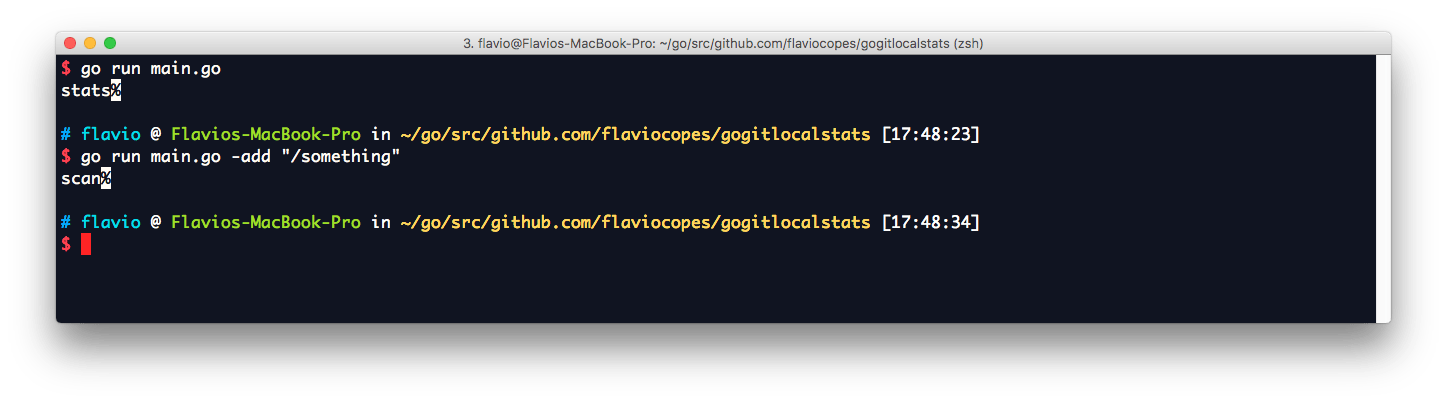

I’ll make a single command do both, using Go command line flags parsing. When passing the -add flag, the command will add a folder to the list. Using the command without flags will generate the graph. I’ll limit the dataset timeframe to the last 6 months, to avoid dumping too much data all at once to the user.

Let’s write a simple skeleton for this separation of concerns:

package main

import (

"flag"

)

// scan given a path crawls it and its subfolders

// searching for Git repositories

func scan(path string) {

print("scan")

}

// stats generates a nice graph of your Git contributions

func stats(email string) {

print("stats")

}

func main() {

var folder string

var email string

flag.StringVar(&folder, "add", "", "add a new folder to scan for Git repositories")

flag.StringVar(&email, "email", "[email protected]", "the email to scan")

flag.Parse()

if folder != "" {

scan(folder)

return

}

stats(email)

}

Part 1: Acquire a list of folders to scan

The algorithm I’ll follow for this first part is pretty simple:

This part of the program is divided in 2 subparts. In the first, I’ll scan the folder passed as argument recursively in search for repositories. I’ll store a list of repositories folders in a file stored in the home directory, called .gogitlocalstats.

Let’s see how scan() can be filled. It’s basically 3 lines of code, beside some output generation:

// scan scans a new folder for Git repositories

func scan(folder string) {

fmt.Printf("Found folders:\n\n")

repositories := recursiveScanFolder(folder)

filePath := getDotFilePath()

addNewSliceElementsToFile(filePath, repositories)

fmt.Printf("\n\nSuccessfully added\n\n")

}This is the workflow:

- we get a slice of strings from

recursiveScanFolder() - we get the path of the dot file we’re going to write to.

- we write the slice contents to the file

Let’s start by examining 1), scanning the folder. I wrote a detailed tutorial on how to scan a folder with Go if you want to learn more about the various options available.

I’m not going to use filepath.Walk because it would go into every single folder. With ioutil.Readdir we have more control. I’ll skip vendor and node_modules folders, which can contain a huge amount of folders which I’m not interested in, and I’ll also skip .git folders, but when I find one, I add it to my slice:

// scanGitFolders returns a list of subfolders of `folder` ending with `.git`.

// Returns the base folder of the repo, the .git folder parent.

// Recursively searches in the subfolders by passing an existing `folders` slice.

func scanGitFolders(folders []string, folder string) []string {

// trim the last `/`

folder = strings.TrimSuffix(folder, "/")

f, err := os.Open(folder)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

files, err := f.Readdir(-1)

f.Close()

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

var path string

for _, file := range files {

if file.IsDir() {

path = folder + "/" + file.Name()

if file.Name() == ".git" {

path = strings.TrimSuffix(path, "/.git")

fmt.Println(path)

folders = append(folders, path)

continue

}

if file.Name() == "vendor" || file.Name() == "node_modules" {

continue

}

folders = scanGitFolders(folders, path)

}

}

return folders

}It explicitly avoids going into folders called vendor or node_modules since those folders can be huge and usually you don’t put your Git repositories in there, we can safely ignore them.

As you can see this is a recursive function, and it’s started by this other function, which passes it an empty slice of strings, to start with:

// recursiveScanFolder starts the recursive search of git repositories

// living in the `folder` subtree

func recursiveScanFolder(folder string) []string {

return scanGitFolders(make([]string, 0), folder)

}Part 2) of the workflow is getting the path of the dotfile containing our database of repos paths:

// getDotFilePath returns the dot file for the repos list.

// Creates it and the enclosing folder if it does not exist.

func getDotFilePath() string {

usr, err := user.Current()

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

dotFile := usr.HomeDir + "/.gogitlocalstats"

return dotFile

}This function uses the os/user package’s Current function to get the current user, which is a struct defined as

// User represents a user account.

type User struct {

// Uid is the user ID.

// On POSIX systems, this is a decimal number representing the uid.

// On Windows, this is a security identifier (SID) in a string format.

// On Plan 9, this is the contents of /dev/user.

Uid string

// Gid is the primary group ID.

// On POSIX systems, this is a decimal number representing the gid.

// On Windows, this is a SID in a string format.

// On Plan 9, this is the contents of /dev/user.

Gid string

// Username is the login name.

Username string

// Name is the user's real or display name.

// It might be blank.

// On POSIX systems, this is the first (or only) entry in the GECOS field

// list.

// On Windows, this is the user's display name.

// On Plan 9, this is the contents of /dev/user.

Name string

// HomeDir is the path to the user's home directory (if they have one).

HomeDir string

}We’re interested in the HomeDir property to get the full path to our dotfile:

dotFile := usr.HomeDir + "/.gogitlocalstats"So, now we have a list of repos, a file to write them to, and the next step for scan() is to store them, without adding duplicate lines.

The process is

- parse the existing repos stored in the file to a slice

- add the new items to the slice, without adding duplicates

- store the slice to the file, overwriting the existing content

This is the job of addNewSliceElementsToFile():

// addNewSliceElementsToFile given a slice of strings representing paths, stores them

// to the filesystem

// addNewSliceElementsToFile given a slice of strings representing paths, stores them

// to the filesystem

func addNewSliceElementsToFile(filePath string, newRepos []string) {

existingRepos := parseFileLinesToSlice(filePath)

repos := joinSlices(newRepos, existingRepos)

dumpStringsSliceToFile(repos, filePath)

}First thing this does is calling parseFileLinesToSlice(), which takes a file path string, and returns a slice of string with the contents of the file. Nothing too much specific:

// parseFileLinesToSlice given a file path string, gets the content

// of each line and parses it to a slice of strings.

func parseFileLinesToSlice(filePath string) []string {

f := openFile(filePath)

defer f.Close()

var lines []string

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(f)

for scanner.Scan() {

lines = append(lines, scanner.Text())

}

if err := scanner.Err(); err != nil {

if err != io.EOF {

panic(err)

}

}

return lines

}This calls openFile(), which given a file path string opens the file and returns it.

// openFile opens the file located at `filePath`. Creates it if not existing.

func openFile(filePath string) *os.File {

f, err := os.OpenFile(filePath, os.O_APPEND|os.O_WRONLY, 0755)

if err != nil {

if os.IsNotExist(err) {

// file does not exist

_, err = os.Create(filePath)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

} else {

// other error

panic(err)

}

}

return f

}In this case it tries to open our dotfile. If there’s an error, and the error tells us that the file does not exist (using os.IsNotExist()), we create the file using os.Create(), so we can start filling it with the repositories scanned. It returns the open file descriptor.

addNewSliceElementsToFile() after getting the file descriptor immediately defers f.Close() to close the file after the function is done. It then calls parseFileLinesToSlice(), an utility function that parses each line of a file to a strings slice.

joinSlices() then given 2 slices, adds the content of the first to the second, only if the content did not exist yet. This prevents duplicate lines.

Put:

// joinSlices adds the element of the `new` slice

// into the `existing` slice, only if not already there

func joinSlices(new []string, existing []string) []string {

for _, i := range new {

if !sliceContains(existing, i) {

existing = append(existing, i)

}

}

return existing

}

// sliceContains returns true if `slice` contains `value`

func sliceContains(slice []string, value string) bool {

for _, v := range slice {

if v == value {

return true

}

}

return false

}Last thing is the call to dumpStringsSliceToFile(), which given a slice of strings, and a file path, writes that slice to the file with each string on a new line:

// dumpStringsSliceToFile writes content to the file in path `filePath` (overwriting existing content)

func dumpStringsSliceToFile(repos []string, filePath string) {

content := strings.Join(repos, "\n")

ioutil.WriteFile(filePath, []byte(content), 0755)

}Here’s the fully working whole content of this first part:

I put this in a separate file, for clarity, called scan.go (in the same folder as main.go)

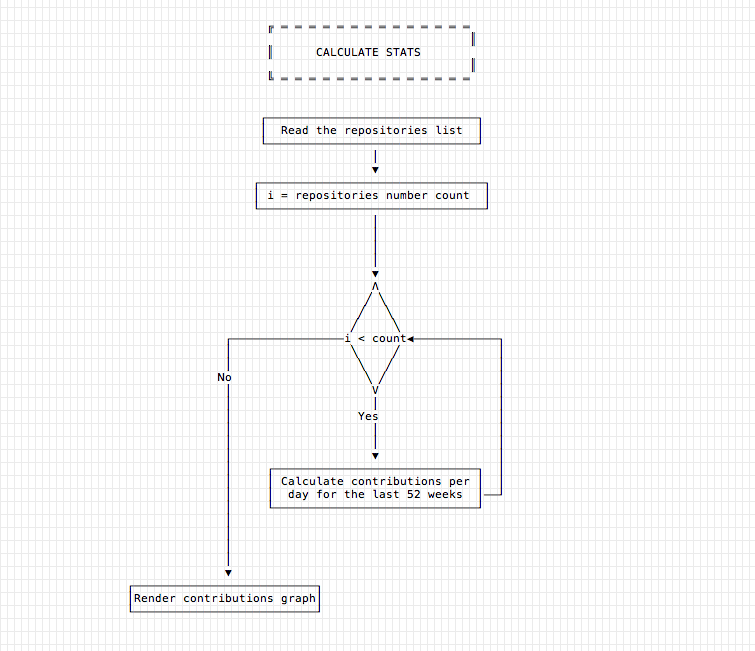

Part 2: Generate the stats

Second part now: generate the stats!

I work on a separate file as well, called stats.go.

In this file I’m going to use a dependency called go-git which is available on GitHub at https://github.com/src-d/go-git. It abstracts the details of dealing with the Git internal representation of commits, exposes a nice API, and it’s self-contained (doesn’t need external libs like the libgit2 bindings do), which for my program is a good compromise.

Let’s implement stats() with 2 function calls:

// stats calculates and prints the stats.

func stats(email string) {

commits := processRepositories(email)

printCommitsStats(commits)

}- get the list of commits

- given the commits, generate the graph

Looks simple enough.

// processRepositories given a user email, returns the

// commits made in the last 6 months

func processRepositories(email string) map[int]int {

filePath := getDotFilePath()

repos := parseFileLinesToSlice(filePath)

daysInMap := daysInLastSixMonths

commits := make(map[int]int, daysInMap)

for i := daysInMap; i > 0; i-- {

commits[i] = 0

}

for _, path := range repos {

commits = fillCommits(email, path, commits)

}

return commits

}Very easy:

- get the dot file path

- parse the lines of the file to a list (slice) of repositories

- fills a

commitsmapwith 0 integer values - iterates over the repositories and fills the

commitsmap

I reuse getDotFilePath() and parseFileLinesToSlice() from the scan.go file. Since the package is the same, I don’t have to do anything, they are available for use.

Here is the fillCommits() implementation:

// fillCommits given a repository found in `path`, gets the commits and

// puts them in the `commits` map, returning it when completed

func fillCommits(email string, path string, commits map[int]int) map[int]int {

// instantiate a git repo object from path

repo, err := git.PlainOpen(path)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

// get the HEAD reference

ref, err := repo.Head()

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

// get the commits history starting from HEAD

iterator, err := repo.Log(&git.LogOptions{From: ref.Hash()})

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

// iterate the commits

offset := calcOffset()

err = iterator.ForEach(func(c *object.Commit) error {

daysAgo := countDaysSinceDate(c.Author.When) + offset

if c.Author.Email != email {

return nil

}

if daysAgo != outOfRange {

commits[daysAgo]++

}

return nil

})

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

return commits

}daysInLastSixMonths is a constant defined as const daysInLastSixMonths = 183.

outOfRange is a constant as well, defined as const outOfRange = 99999 which contrary to daysInLastSixMonths has no real meaning. It’s set as the return value of countDaysSinceDate() when the commit is older than 6 months, our data analysis interval.

object is provided by the go-git package, by importing gopkg.in/src-d/go-git.v4/plumbing/object.

I add an offset to the “daysAgo” calculation because of the way the GitHub-like graph works: each row represents a day name (starting from sunday), and each row represents a week. I fill the current week with “fake data”.

countDaysSinceDate() returns how many days ago the commit was made. I reset the current date to the exact start of the day (00:00:00) to avoid hours being part of the equation. The timezone is inferred from the system.

// getBeginningOfDay given a time.Time calculates the start time of that day

func getBeginningOfDay(t time.Time) time.Time {

year, month, day := t.Date()

startOfDay := time.Date(year, month, day, 0, 0, 0, 0, t.Location())

return startOfDay

}

// countDaysSinceDate counts how many days passed since the passed `date`

func countDaysSinceDate(date time.Time) int {

days := 0

now := getBeginningOfDay(time.Now())

for date.Before(now) {

date = date.Add(time.Hour * 24)

days++

if days > daysInLastSixMonths {

return outOfRange

}

}

return days

}calcOffset() is used to determine the correct place of a commit in our commits map, to be easily shown in the console render.

// calcOffset determines and returns the amount of days missing to fill

// the last row of the stats graph

func calcOffset() int {

var offset int

weekday := time.Now().Weekday()

switch weekday {

case time.Sunday:

offset = 7

case time.Monday:

offset = 6

case time.Tuesday:

offset = 5

case time.Wednesday:

offset = 4

case time.Thursday:

offset = 3

case time.Friday:

offset = 2

case time.Saturday:

offset = 1

}

return offset

}We’re now done with processing the commits. We now have a map of commits, we can print it. Here’s the operation center:

// printCommitsStats prints the commits stats

func printCommitsStats(commits map[int]int) {

keys := sortMapIntoSlice(commits)

cols := buildCols(keys, commits)

printCells(cols)

}- sort the map

- generate the columns

- print each column

Sort the map

// sortMapIntoSlice returns a slice of indexes of a map, ordered

func sortMapIntoSlice(m map[int]int) []int {

// order map

// To store the keys in slice in sorted order

var keys []int

for k := range m {

keys = append(keys, k)

}

sort.Ints(keys)

return keys

}sortMapIntoSlice() takes a map and returns a slice with the map keys ordered by their integer value. This is used to print the map properly sorted.

Generate the columns

// buildCols generates a map with rows and columns ready to be printed to screen

func buildCols(keys []int, commits map[int]int) map[int]column {

cols := make(map[int]column)

col := column{}

for _, k := range keys {

week := int(k / 7) //26,25...1

dayinweek := k % 7 // 0,1,2,3,4,5,6

if dayinweek == 0 { //reset

col = column{}

}

col = append(col, commits[k])

if dayinweek == 6 {

cols[week] = col

}

}

return cols

}buildCols() takes the keys slice we generated in sortMapIntoSlice() and the map. It creates a new map, instead of using the days as keys, it uses weeks. The column type is defined as a slice of integers: type column []int.

The week is determined by dividing the day index by 7, and which day of the week is it, is easy to get with a module operation k % 7. When the day of the week is sunday, we create a new column and we fill it, and when it’s saturday, we add the week to the columns map.

Print the cells

// printCells prints the cells of the graph

func printCells(cols map[int]column) {

printMonths()

for j := 6; j >= 0; j-- {

for i := weeksInLastSixMonths + 1; i >= 0; i-- {

if i == weeksInLastSixMonths+1 {

printDayCol(j)

}

if col, ok := cols[i]; ok {

//special case today

if i == 0 && j == calcOffset()-1 {

printCell(col[j], true)

continue

} else {

if len(col) > j {

printCell(col[j], false)

continue

}

}

}

printCell(0, false)

}

fmt.Printf("\n")

}

}printCells(), first calls printMonths() to print the months names line. Then for each different subsequent line (day of the week) it processes each week and calls printCell(), passing the value and if it’s today or not.

If it’s the first column, it calls printDayCol() to print the day name.

// printMonths prints the month names in the first line, determining when the month

// changed between switching weeks

func printMonths() {

week := getBeginningOfDay(time.Now()).Add(-(daysInLastSixMonths * time.Hour * 24))

month := week.Month()

fmt.Printf(" ")

for {

if week.Month() != month {

fmt.Printf("%s ", week.Month().String()[:3])

month = week.Month()

} else {

fmt.Printf(" ")

}

week = week.Add(7 * time.Hour * 24)

if week.After(time.Now()) {

break

}

}

fmt.Printf("\n")

}Here’s printMonths(). It goes to the beginning of the history we’re analyzing, and increments week-by-week. If the month changes when going to the next week, it prints it. Breaks when I get over the current date.

printDayCol() is very simple, given a day row index, it prints the day name:

// printDayCol given the day number (0 is Sunday) prints the day name,

// alternating the rows (prints just 2,4,6)

func printDayCol(day int) {

out := " "

switch day {

case 1:

out = " Mon "

case 3:

out = " Wed "

case 5:

out = " Fri "

}

fmt.Printf(out)

}printCell(), listed below, calculates the correct escape sequence depending on the amount of commits in a cell, and also standardizes the cell width, depending on the number of digits of the number printed. And at the end, it prints the cell to io.Stdout:

// printCell given a cell value prints it with a different format

// based on the value amount, and on the `today` flag.

func printCell(val int, today bool) {

escape := "\033[0;37;30m"

switch {

case val > 0 && val < 5:

escape = "\033[1;30;47m"

case val >= 5 && val < 10:

escape = "\033[1;30;43m"

case val >= 10:

escape = "\033[1;30;42m"

}

if today {

escape = "\033[1;37;45m"

}

if val == 0 {

fmt.Printf(escape + " - " + "\033[0m")

return

}

str := " %d "

switch {

case val >= 10:

str = " %d "

case val >= 100:

str = "%d "

}

fmt.Printf(escape+str+"\033[0m", val)

}Here is the complete code for stats.go, with the contents of this second part of the program:

Here is what you’ll get when running it:

download all my books for free

- javascript handbook

- typescript handbook

- css handbook

- node.js handbook

- astro handbook

- html handbook

- next.js pages router handbook

- alpine.js handbook

- htmx handbook

- react handbook

- sql handbook

- git cheat sheet

- laravel handbook

- express handbook

- swift handbook

- go handbook

- php handbook

- python handbook

- cli handbook

- c handbook

subscribe to my newsletter to get them

Terms: by subscribing to the newsletter you agree the following terms and conditions and privacy policy. The aim of the newsletter is to keep you up to date about new tutorials, new book releases or courses organized by Flavio. If you wish to unsubscribe from the newsletter, you can click the unsubscribe link that's present at the bottom of each email, anytime. I will not communicate/spread/publish or otherwise give away your address. Your email address is the only personal information collected, and it's only collected for the primary purpose of keeping you informed through the newsletter. It's stored in a secure server based in the EU. You can contact Flavio by emailing [email protected]. These terms and conditions are governed by the laws in force in Italy and you unconditionally submit to the jurisdiction of the courts of Italy.