JavaScript Functions

Learn all about functions, from the general overview to the tiny details that will improve how you use them

TypeScript Masterclass

AVAILABLE NOW

- Introduction

- Syntax

- Parameters

- Return values

- Nested functions

- Object Methods

- this in Arrow Functions

- IIFE, Immediately Invocated Function Expressions

- Function Hoisting

Introduction

Everything in JavaScript happens in functions.

A function is a block of code, self contained, that can be defined once and run any times you want.

A function can optionally accept parameters, and returns one value.

Functions in JavaScript are objects, a special kind of objects: function objects. Their superpower lies in the fact that they can be invoked.

In addition, functions are said to be first class functions because they can be assigned to a value, and they can be passed as arguments and used as a return value.

Syntax

Let’s start with the “old”, pre-ES6/ES2015 syntax. Here’s a function declaration:

I use

fooandbaras random names. Enter any kind of name to replace them.

function dosomething(foo) {

// do something

}(now, in post ES6/ES2015 world, referred as a regular function)

Functions can be assigned to variables (this is called a function expression):

const dosomething = function(foo) {

// do something

}Named function expressions are similar, but play nicer with the stack call trace, which is useful when an error occurs - it holds the name of the function:

const dosomething = function dosomething(foo) {

// do something

}ES6/ES2015 introduced arrow functions, which are especially nice to use when working with inline functions, as parameters or callbacks:

const dosomething = foo => {

//do something

}Arrow functions have an important difference from the other function definitions above, we’ll see which one later as it’s an advanced topic.

Parameters

A function can have one or more parameters.

const dosomething = () => {

//do something

}

const dosomethingElse = foo => {

//do something

}

const dosomethingElseAgain = (foo, bar) => {

//do something

}Starting with ES6/ES2015, functions can have default values for the parameters:

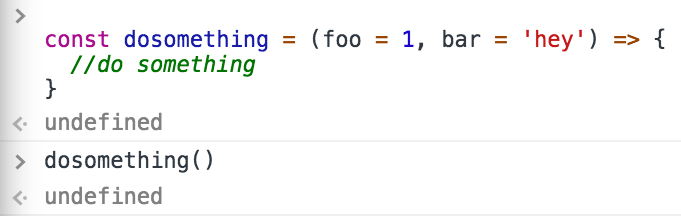

const dosomething = (foo = 1, bar = 'hey') => {

//do something

}This allows you to call a function without filling all the parameters:

dosomething(3)

dosomething()ES2018 introduced trailing commas for parameters, a feature that helps reducing bugs due to missing commas when moving around parameters (e.g. moving the last in the middle):

const dosomething = (foo = 1, bar = 'hey') => {

//do something

}

dosomething(2, 'ho!')You can wrap all your arguments in an array, and use the spread operator operator when calling the function:

const dosomething = (foo = 1, bar = 'hey') => {

//do something

}

const args = [2, 'ho!']

dosomething(...args)With many parameters, remembering the order can be difficult. Using objects, destructuring allows to keep the parameter names:

const dosomething = ({ foo = 1, bar = 'hey' }) => {

//do something

console.log(foo) // 2

console.log(bar) // 'ho!'

}

const args = { foo: 2, bar: 'ho!' }

dosomething(args)Return values

Every function returns a value, which by default is undefined.

Any function is terminated when its lines of code end, or when the execution flow finds a return keyword.

When JavaScript encounters this keyword it exits the function execution and gives control back to its caller.

If you pass a value, that value is returned as the result of the function:

const dosomething = () => {

return 'test'

}

const result = dosomething() // result === 'test'You can only return one value.

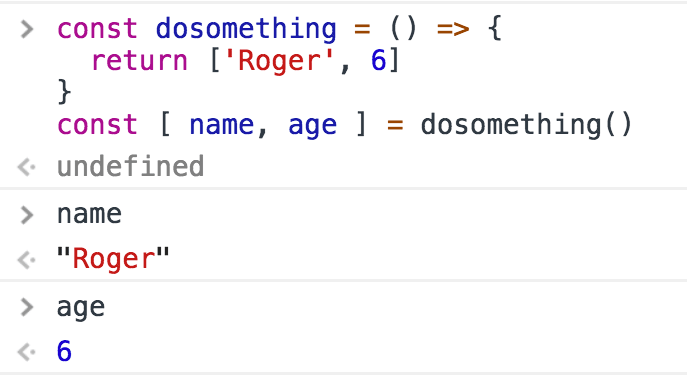

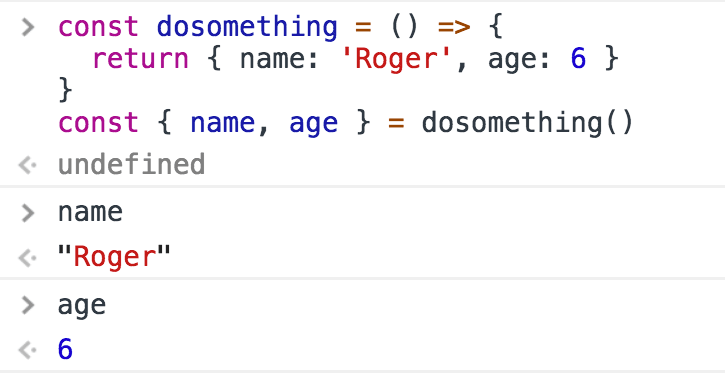

To simulate returning multiple values, you can return an object literal, or an array, and use a destructuring assignment when calling the function.

Using arrays:

Using objects:

Nested functions

Functions can be defined inside other functions:

const dosomething = () => {

const dosomethingelse = () => {

//some code here

}

dosomethingelse()

return 'test'

}The nested function is scoped to the outside function, and cannot be called from the outside.

This means that dosomethingelse() is not reachable from outside dosomething():

const dosomething = () => {

const dosomethingelse = () => {

//some code here

}

dosomethingelse()

return 'test'

}

dosomethingelse() //ReferenceError: dosomethingelse is not definedThis is very useful because we can create encapsulated code that is limited in its scope by the outer function it’s defined in.

We could have 2 function define a function with the same name, inside them:

const bark = () => {

const dosomethingelse = () => {

//some code here

}

dosomethingelse()

return 'test'

}

const sleep = () => {

const dosomethingelse = () => {

//some code here

}

dosomethingelse()

return 'test'

}and most importantly you don’t have to think about overwriting existing functions and variables defined inside other functions.

Object Methods

When used as object properties, functions are called methods:

const car = {

brand: 'Ford',

model: 'Fiesta',

start: function() {

console.log(`Started`)

}

}

car.start()this in Arrow Functions

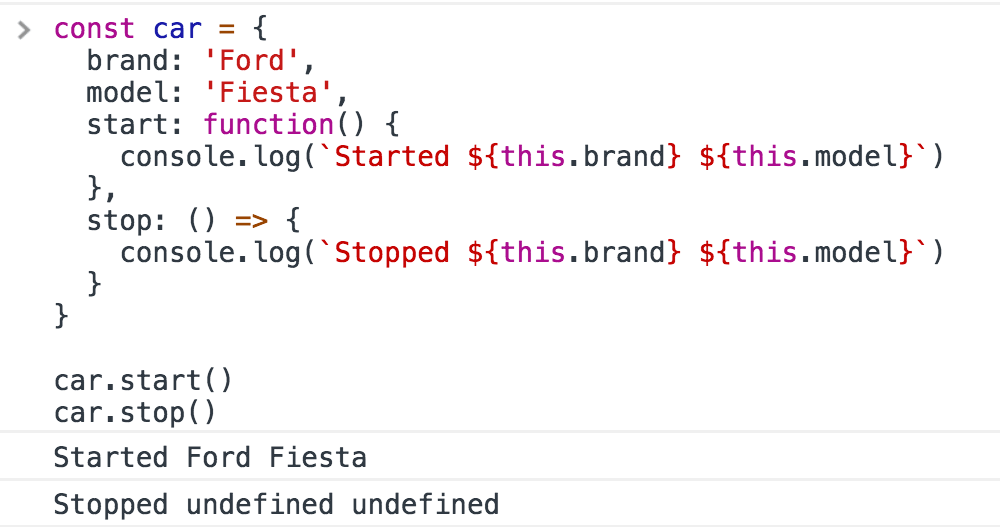

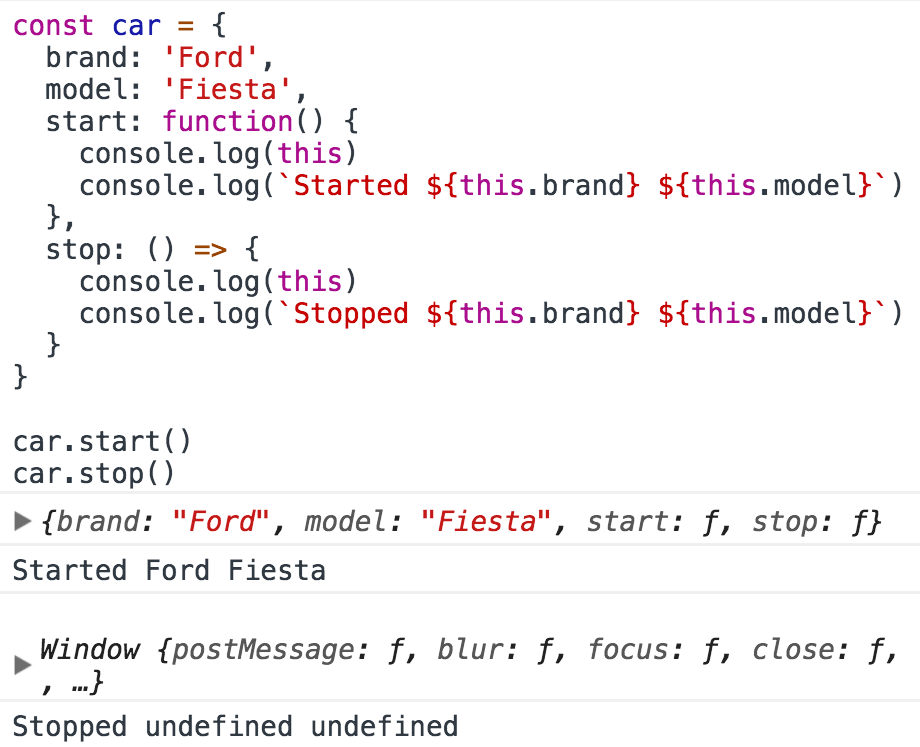

There’s an important behavior of Arrow Functions vs regular Functions when used as object methods. Consider this example:

const car = {

brand: 'Ford',

model: 'Fiesta',

start: function() {

console.log(`Started ${this.brand} ${this.model}`)

},

stop: () => {

console.log(`Stopped ${this.brand} ${this.model}`)

}

}The stop() method does not work as you would expect.

This is because the handling of this is different in the two functions declarations style. this in the arrow function refers to the enclosing function context, which in this case is the window object:

this, which refers to the host object using function()

This implies that arrow functions are not suitable to be used for object methods and constructors (arrow function constructors will actually raise a TypeError when called).

IIFE, Immediately Invocated Function Expressions

An IIFE is a function that’s immediately executed right after its declaration:

;(function dosomething() {

console.log('executed')

})()You can assign the result to a variable:

const something = (function dosomething() {

return 'something'

})()They are very handy, as you don’t need to separately call the function after its definition.

See my post dedicated to them.

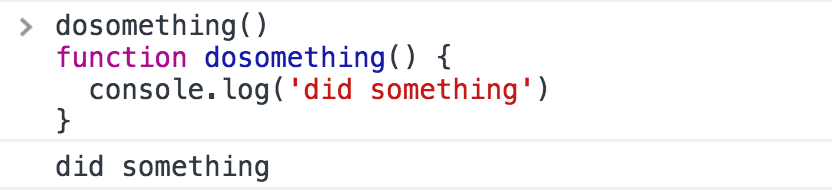

Function Hoisting

JavaScript before executing your code reorders it according to some rules.

Functions in particular are moved at the top of their scope. This is why it’s legal to write

dosomething()

function dosomething() {

console.log('did something')

}

Internally, JavaScript moves the function before its call, along with all the other functions found in the same scope:

function dosomething() {

console.log('did something')

}

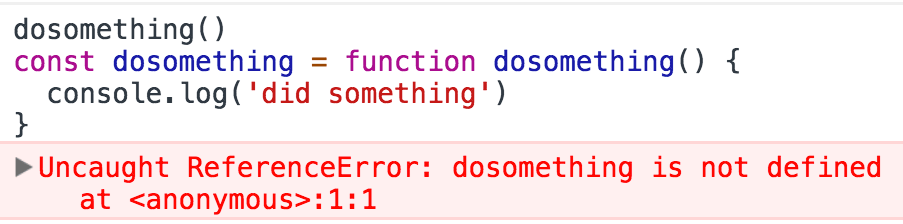

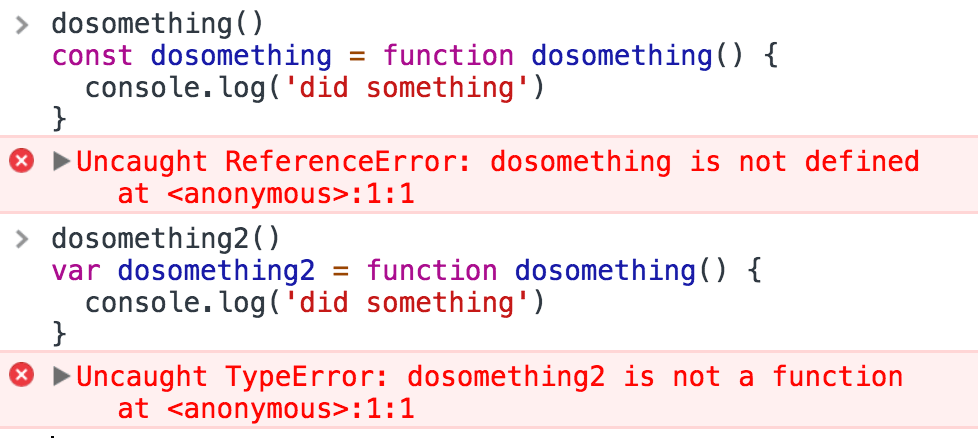

dosomething()Now, if you use named function expressions, since you’re using variables something different happens. The variable declaration is hoisted, but not the value, so not the function.

dosomething()

const dosomething = function dosomething() {

console.log('did something')

}Not going to work:

This is because what happens internally is:

const dosomething

dosomething()

dosomething = function dosomething() {

console.log('did something')

}The same happens for let declarations. var declarations do not work either, but with a different error:

This is because var declarations are hoisted and initialized with undefined as a value, while const and let are hoisted but not initialized.

I wrote 20 books to help you become a better developer:

- JavaScript Handbook

- TypeScript Handbook

- CSS Handbook

- Node.js Handbook

- Astro Handbook

- HTML Handbook

- Next.js Pages Router Handbook

- Alpine.js Handbook

- HTMX Handbook

- React Handbook

- SQL Handbook

- Git Cheat Sheet

- Laravel Handbook

- Express Handbook

- Swift Handbook

- Go Handbook

- PHP Handbook

- Python Handbook

- Linux/Mac CLI Commands Handbook

- C Handbook